Tuckerton Oyster Restoration Site Doubles in Size

Port Republic, N.J. - A flashlight beam illuminated what appeared to be swirling dots of fine-ground pepper flakes settling at the bottom of a clear bottle filled with chilled bay water.

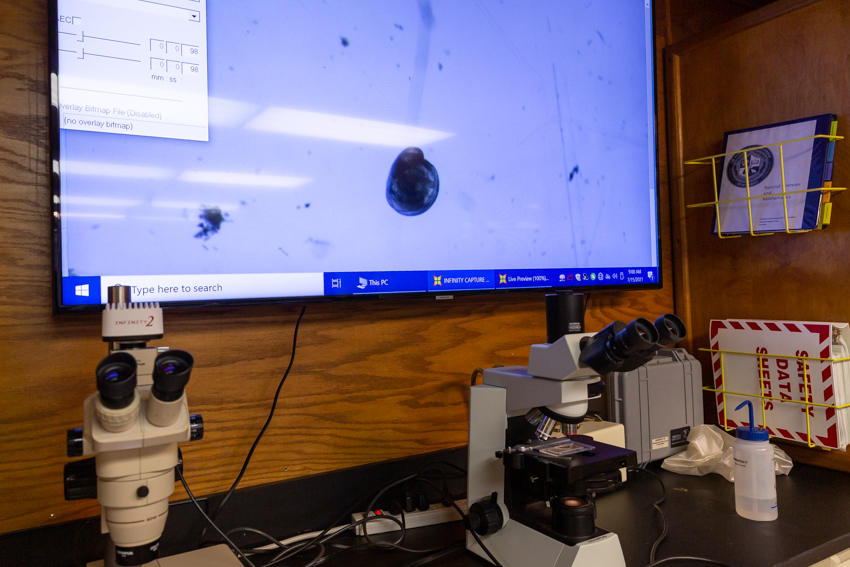

A few minutes later, the nearly invisible specks were resting in a droplet of water on a glass slide and appeared at 10x magnification on a TV monitor linked to a microscope. The flakes are eyed oyster larvae, and within two weeks, they will be at the bottom of the bay on an oyster reef. In that short window of time, marine researchers and commercial oyster farmers will join forces to prepare for the annual oyster planting on the Tuckerton oyster reef, a restoration site.

Students and staff at the Stockton University Marine Field Station gathered to watch the larvae swim across the screen. With a magnified view, students could see the hair-like cilia on the velum organ, which propels an oyster through the water and helps it feed on microalgae.

This summer, fifth-generation oyster farmer Dale Parsons, of Parsons Seafood in Tuckerton, poured 11 million eyed larvae—just like the ones students viewed under the microscope—into tanks at his mariculture center at Great Bay Marina. Cages of whelk shells and recycled oyster shells from Long Beach Island restaurants filled the tanks, and after about two weeks of swimming freely, the larvae grew a foot, settled to the bottom and crawled to the shell they will anchor onto for the remainder of their lives. This aquaculture process is called remote setting, since the beginning of the oyster lifecycle takes place in a tank in optimal conditions free from predation.

Once the shells are speckled with growing oysters, it’s time for planting at the reef site. The cages are emptied onto a barge, and at the reef site, the shell pile in planted in the bay with water power from a hose that pushes the shells overboard.

The first round this summer planted 1,134 bushels to cover about half an acre of a 1-acre plot. A future second planting will add about the same amount.

Recycling Restaurant Shells into Reef Habitat

During the peak of summer tourism season, before COVID-19, Brianna Triebel, a junior Marine Science major, had loaded her car with two baskets of oyster shells from the Daymark Bar and Restaurant in Barnegat Light after work each night, and then delivered them to Parsons Seafood in Tuckerton.

Instead of going into the trash, empty half shells from customers’ plates were collected for a recycling program that puts them back into the Barnegat Bay to restore the ecosystem.

The Follow the Shell oyster recycling program works with 15 restaurants on Long Beach Island, and a dedicated truck picks up shells three times per week and drops them off at a curing site during the summer.

Angela Andersen ‘91, who is the recycling and sustainability director for Long Beach Township, oversees the program, and the Jetty Rock Foundation manages the marketing and outreach to raise funds to sustain the reef.

At Stockton’s Marine Field Station, Triebel gathered around a table with fellow Marine Science majors to count spat on a subsample of whelk shells that are part of a study to see if oysters can benefit eelgrass growth.

“I get to see the bigger picture and help the cycle continue,” Triebel said of her experience doing oyster research as she examined the tiny flecks on a shell.

In two to three years, those flecks will grow to market size. However, the oysters involved in Stockton’s research projects aren’t for eating; their purpose is to show scientists how restoration can work.

Field Station and Aquarium Exhibit to Offer a Window into Reef Ecology

A telescope on the second floor of the Long Beach Township (LBT) Field Station in Holgate is aimed over the bay and just to the right of the Tuckerton water tower where the Tuckerton Reef is located beneath the surface.

Five years ago, the field station was a vision in Angela Andersen’s mind along with dozens of ideas for ways it could help to educate and inspire the local community to be ambassadors for Long Beach Island’s coastal environment, recycling and restoration of the Barnegat Bay by way of oysters.

With open spaces trust money and support from Mayor Joseph Mancini, the field station is now a hub for science and education and stands alongside 22 acres of preserved saltmarsh known as Clam Cove Reserve. During Sandy, an overwash pushed sand from the ocean side toward the bay and covered the marsh. The Ocean County Natural Lands Trust Fund and Long Beach Township purchased this land to protect it from development.

The oyster has been a driver of many initiatives for Andersen who manages the field station operations.

After taking in the panoramic view of the reef’s setting in the bay, guests can head downstairs to the laboratory space where the Stockton Aquarium and Aquaculture Club is building a window into the reef habitat to give the public a unique view of a what is otherwise hidden.

Usama Chaudhri ’21, a Marine Science graduate and a founding member of the Aquarium and Aquaculture Club, had never maintained oysters in captivity, but a field experience sampling marine life during “Intro to Marine Biology” put oysters on his radar when the class passed over the reef site.

Through an aquarium display, Chaudhri is bringing a view of the underwater world to guests who visit the LBT field station.

“We want to create a slice of the oyster reef. The water here is so murky, so it’s really difficult for us to see what it looks like if you look down into the water from a boat,” he explained.

“We also want to show what we are trying to accomplish with the reef restoration project where we take recycled oyster shells and seed them with larvae,” he added.

Guests were astonished by the visible growth from a clusters of oysters growing off of recycled shells planted back in 2019, Chaudhri said.

When giving tours of the aquarium exhibit, “we can say these oysters came from right over there,” Chaudhri said.

Lessons Can Be Learned from Listening to Bivalves

Wild oysters in the bay cannot sustain the reef through natural breeding, so scientists are adding recycled shells with remotely-set oysters and then listening to the ecosystem by gathering and analyzing data.

“Even though more and more oysters are present in Barnegat Bay through these projects and aquaculture, the amount of natural set we are observing is still not enough to sustain the reef. We are adding oysters as we have funding and availability to do so,” said Christine Thompson, assistant professor of Marine Science.

Evidence of the restoration’s success can be seen by bringing up a sample of shells from the reef during monitoring and looking for spat from wild oysters.

“For natural set, this year we planted some bare oyster and whelk shell and saw about 1 spat per oyster shell and 5 per whelk shell, which is really promising for self-sustainability,” said Thompson.

Whelk shells have a greater surface area and provide more space for oysters to grow.

In the Stockton Marine Field Station laboratory, students rinse and whisk away debris with paint brushes before counting spat on a subsample of shells.

“We do a lot of math to get one number, which is the percentage of larvae that have attached to the shells. That number is the spat setting ratio and it helps to determine how much larvae is needed and how many shells [for future work],” Thompson explained.

The number that the researchers ultimately want to determine is how many oysters it takes to bring the bay back to historic conditions when oysters could maintain a healthy and diverse ecosystem through filter feeding.

“We are trying to estimate the water quality improvements made by the oysters we planted over the years. It takes about two years for oysters to get big enough to start filtering large volumes of water,” explained Thompson.

Monitoring also looks at marine life changes. Fish were quick to find the reef.

“We've seen increased populations of oyster toadfish and black sea bass on the reef compared to off of the reef. We overall see more species on the reef,” said Thompson.

Can Oysters Help Eelgrass Take Root for a Comeback?

At Bunting Sedge in the Barnegat Bay, oysters were planted experimentally in a very different way from the Tuckerton Reef to see how the oyster may be able to help eelgrass take root to make a comeback.

Eelgrass is as critical to the bay ecosystem as it is finicky to grow and understudied by researchers.

Elizabeth “Dr. Z” Lacey, associate professor of Marine Science, is studying how an underwater berm of oysters might be able to act as a wave break to increase eelgrass seed retention.

“If oysters can be planted as a berm, they can slow currents down enough that eelgrass seed won’t get washed away. If this is the reason why there is no eelgrass growing in the area, it can assist restoration efforts,” she explained.

Lacey’s eelgrass restoration study has four plots with two containing just seed and two containing seed with a berm of spat on whelk shells that was planted in July.

“The idea is that there is positive feedback between an eelgrass habitat and an oyster habitat. The shells can stabilize the soil, so it doesn’t wash over onto the eelgrass, and the eelgrass is going to stabilize the soil so it doesn’t wash back over onto the oysters themselves,” she explained.

The filtration capacity and the habitat that the oysters provide will also benefit the plots that are associated with the oyster berm.

A bay without eelgrass has consequences. “Eelgrass is a nursery habitat, protects the shoreline, prevents erosion and has economic value because people coming in to go fishing need that kind of ecosystem to support the wildlife,” explained Lacey.

The construction of the Route 72 causeway bridge connecting Long Beach Island to the mainland caused unavoidable losses of eelgrass, but environmental mitigation projects attempt to make up for the loss. Lacey’s study looks to the oyster as a potential way to aid this restoration work.

Eelgrasses “require very particular types of water conditions, certain depths, temperature and soil characteristics,” which makes planting new beds a challenge, said Lacey.

For example, if the water is too deep, then the grasses won’t get enough sunlight, and if the water is too shallow, then the temperature may overheat the grasses, and if the current is too strong, then the grasses cannot take root.

Lacey and her students harvested seed heads sustainably from donor beds designated for Route 72 restoration work and placed them in tanks for the summer. “The seeds eventually fall out of what they call the spath, which are the reproductive stems holding the seeds,” she said.

Seeds will be planted at the four research plots, known as a dual habitat site, this fall. “It takes two years before you have reproductive shoots for seagrasses. We would potentially see growth as soon as next year. May is the beginning of the growing season for eelgrass seed,” she said.

Oysters Steer Restoration

Steve Evert, director of the Marine Field Station, still remembers the first pile

of shells collected by Dave Ambrose, a field research technician, who filled the bed

of his pickup truck with shells from Old Causeway Steak and Oyster House and brought

them to work back in 2015.

Steve Evert, director of the Marine Field Station, still remembers the first pile

of shells collected by Dave Ambrose, a field research technician, who filled the bed

of his pickup truck with shells from Old Causeway Steak and Oyster House and brought

them to work back in 2015.

"From those first local shell recycling efforts to today the concept and the program has grown considerably thanks to the efforts of our partners, especially Long Beach Township and the Jetty rock foundation," said Evert.

Oyster research has revealed a theme of connection to Christine Thompson.

“Oysters connect to each other to build reefs in terms of recruitment, they connect students and the community to this project, and they connect with seagrass to mutually benefit each other,” she said.

Reported by Susan Allen

Below is a slideshow of images from the first planting in 2016 and the following years of research, monitoring and additional plantings.