The Story Behind Stockton

Galloway, N.J. - Often called the “founding mother of Stockton,” Elizabeth Barstow Alton led the

campaign to locate a college in South Jersey in the mid-1960s.

Galloway, N.J. - Often called the “founding mother of Stockton,” Elizabeth Barstow Alton led the

campaign to locate a college in South Jersey in the mid-1960s.

But, as strong and persistent a force as she was, she could not have done it alone. In fact, one of her strengths was knowing how to build coalitions and find partners.

Those partners ranged from schoolchildren who wrote letters, media, businesspeople, clubs and organizations, and powerful state and local politicians who were smart enough to get on board when the Elizabeth Alton train roared through.

Alton talks about her campaign in two books: “The Stockton Story,” published by Stockton in 1983 and “Beauty is Never Enough” a memoir of her life published by the South Jersey Culture & History Center at Stockton in 2021.

The fight to get a university in South Jersey was not an easy one. In 1965 the State Board of Higher Education asked a committee to make recommendations in the northwestern and southeastern parts of the state to locate just one new college.

In February 1966, Alton, who was already prominent in the Miss America Pageant hostess committee and the N.J. Federation of Women’s Clubs, spoke at the Atlantic City Kiwanis Club and promoted the idea of a college in South Jersey.

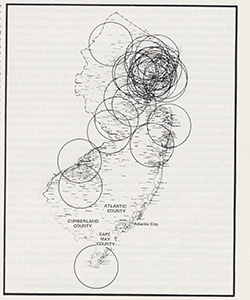

Appearances on the popular Pinky Kravitz radio show, and a visit from prominent Rabbi Aaron Krauss encouraged her to mount a campaign. With friend Mildred Brick, Alton began traveling the state, talking to anyone who would listen. They created a large chart showing the locations of all the colleges in the state and it was hard to argue against her when the map clearly showed the large empty gap in the southeast.

Support grew from Atlantic County into Cape May and Cumberland counties, where there was also interest by the prominent “Committee of 50” in locating the college in the Vineland area.

The Press of Atlantic City and its then editor, Charles Reynolds (who later served on the first Board of Trustees) kept the issue in the news and in front of the public and politicians. James Hayward, then president of Atlantic City Electric Company, actively served as vice-chair of the Citizens Committee for Higher Education, formed to promote the college.

But as support grew locally, political maneuverings in the north attempted to block any progress. Alton was even called suddenly (and she believes suspiciously) to appear for jury duty, preventing her from attending an important meeting in Trenton on the proposal for a new college.

Not to be deterred, Alton met with the new chancellor of higher education in 1967 and hosted a dinner to honor him in Atlantic City in early 1968. The state Board of Higher Education in May 1968 compromised by recommending two new state colleges. But they still needed funding.

Local state Sen. Frank “Hap” Farley, a powerhouse politician whose support was crucial, at first wouldn’t meet with Alton. Alton writes in “Beauty is Never Enough” (p333) that “I determined to secure his full attention and persuade him to work for our college in the legislature by arousing so much public support that a college would become a political necessity.”

When she did just that, Farley came on board full force, blocking a proposed state bond issue for construction until a South Jersey college was included. Legislators called it “Farley’s college.”

Alton and supporters still kept working to convince voters to support the bond issue, which passed in November 1968.

Alton, who was appointed to serve on Stockton’s first Board of Trustees, including a term as chair, notes in “Beauty is Never Enough” (p334) that on its 10th anniversary the college honored the first board of trustees as college founders.

“They were the builders and planners of the college from day one, but they were not the real founders of the college,” Alton wrote. “The people of South Jersey were.”

Still, it was the organizational talents and persistence of Elizabeth Alton who mobilized the people to act. In the foreword to the “The Stockton Story” she wrote:

“This history is meant to be an inspiration to those who dream great dreams but hesitate to take the first steps necessary for their fulfillment… The Stockton Story is a clear example that average people can achieve goals they seek through careful planning, preparation and organization, coupled with the kind of persistence that refuses to accept defeat.”

- By Diane D'Amico