Spotlight On: Sharon Musher

Galloway, N.J. — "It's hard to believe that this is my eighteenth year at Stockton," Sharon Musher said, reflecting on the different classes she has taught at the university.

The history professor teaches a range of courses depending on the needs of the Historical Studies program and works with other programs including the M.A. in American Studies, Women's, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, and Jewish Studies.

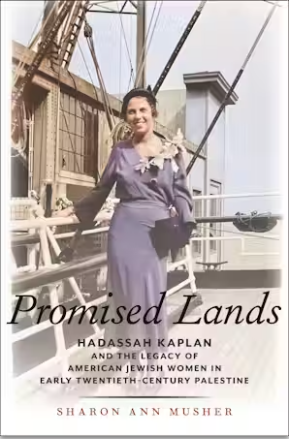

Later this month, Musher's book, "Promised Lands," will be released, a coming-of-age story about her grandmother in the 1930s. Below, she talks about her inspiration for writing it and some gems she discovered along her archival journey.

Can you share a brief description about your book, “Promised Lands”?

"Promised Lands" tells the story of my grandmother, Hadassah Kaplan (later Musher). Hadassah was the second daughter of Rabbi Mordecai Kaplan, who founded Reconstructionism, an American form of Judaism. He also initiated the bat mitzvah, a right-of-passage for Jewish girls, with Hadassah's older sister Judith.

In the summer of 1932, Hadassah was a 19-year-old, unemployed, public school teacher in New York. She joined a small but influential cohort of American Jewish women who studied, worked, and volunteered in British Mandate Palestine. Drawing on a rich family archive of diaries, photographs, and letters, “Promised Lands” argues that for somewhat unconventional American Jewish women, like Hadassah, spending time in Palestine allowed them to challenge cultural norms while still remaining so-called "good" daughters, wives, and mothers. When they returned to the U.S. - as did most in this cohort - they centered Zionism in the Jewish institutions and communities where they taught, volunteered, and fundraised.

How does it relate to your work here at Stockton?

Research informs my teaching. All Historical Studies majors write a thesis for their capstone. My work models that research process.

My book also contributes to a broader project, that inspires my teaching: recovering women's voices. In my GAH 3617: Meanings of Motherhood class, students interview a mother figure (they often choose their own mother or grandmother). For many, this oral history project is a significant one in which they ask questions they never before considered and come to understand the person they interviewed in new ways.

Finally, my teaching at Stockton has introduced me to some wonderful students, some of whom I have been lucky enough to work with as research assistants. For example, last year, I worked with Alexa Novo, who built a terrific website for me, double-checked my footnotes, and helped me to caption photographs. I hope that her work for me gave her skills and insights into academic life and what it takes to publish a book. Certainly, for me, her work was indispensable.

How long have you been working on this piece, and what inspired you to write it?

I've been thinking about this book since the summer before I entered graduate school. I actively began to work on the project about a decade ago after my grandmother passed away and, particularly, when my parents located the records documenting her travels. I was inspired by the archive she left behind. It provided a window both into the Upper West Side and Mandatory Palestine in the early twentieth century. Women's history and the history of people from underrepresented communities are often dismissed or literally discarded. I wanted to preserve Hadassah's story and use it to understand the emerging relationship between American Jewish women and Palestine. I also wanted to be able to explain to my daughters and their generation what Palestine had meant to their ancestors at a moment when, in many circles, Israel and Zionism have become pejorative terms.

Were there any surprising discoveries you made during your research?

Perhaps my most surprising discovery, which I learned through Hadassah's diary – not her letters home to her parents and sisters – was that she had a relationship with a married man who was more than twice her age when she was on the ship enroute to Palestine. Travel created a world between worlds where women, in particular, could push the boundaries of social, cultural, religious, and sexual norms. The movie “Titanic” gives some insight into this type of freedom.

I also learned that although unusual, transatlantic oceanic travel became more affordable for members of the middle and even working class in the early twentieth century. The development of third-class steamship tickets, tourist accommodation, and the guidebook industry helped to make more accessible such travel. By the 1920s, even former immigrants to the U.S. were traveling abroad.

Author, Unscripted

💭 What is something about yourself that may surprise people? My dog, whom I adore, is named after a Jewish gangster - Meyer Lansky – although he basically looks like a teddy bear.

✒️ What advice would you offer aspiring young writers? To have the stamina to write a book, you need to be able to sit in your loneliness, find your voice, and wrestle with alternative perspectives without losing yourself when you receive criticism, which you will. More logistically, take deep breaths, generate a to-do list (multiple lists, actually), figure out what you actually need to do when, and give yourself time – even if it's only a little – to move the project forward each day (and then be kind to yourself when you fail to do that, as you inevitably will).

📖 What is your favorite book and why? One of my favorite books is a historical fiction novel called “The Weight of Ink” by Rachel Kadish. This work travels through time (from the 1600s to the 2000s) and space (Amsterdam, Israel and London) while foregrounding the stories of two brilliant women living in London: a 17th-century Jewish philosopher – well before women were able to occupy such ranks - and an aging historian with advancing Parkinson's disease. There is a recovered trove of 300-year-old documents, the politics of academics struggling to tell their story, coupled with a rich retelling of the historical world they sought to recover. The book uses fiction to explore female agency, Jewish history and the academic enterprise in ways that resonate strongly with my own work.

Was there a particular story or individual that resonated with you most?

There are many intergenerational exchanges in the book that resonated with me, both as a mother and as a daughter.

There is a poignant exchange between Hadassah and her father in Hebrew, the language they used to correspond with one another, a language that was only then being revived as a spoken tongue after serving as a language for prayer, literature, and study for two thousand years.

Mordecai eagerly waited for his daughter to write to him in Hebrew. When she finally did, he responded by expressing his existential loneliness as a Jew in the United States and asking if he should move to "Eretz Israel" (the Land of Israel). "Despite the large number of Jews here," he writes, "I am like a juniper in the desert due to the wide distance between my views and aspirations and the views and aspirations of those with whom I interact at the various institutions in which I invest all my energy."

The young Hadassah answers him as only a teenager might (she is 20 at the time). She suggests that her parents might enjoy Palestine, where her mama might garden, and her papa might teach at the university. When Mordecai pushes back, suggesting that he needed to remain focused on the struggles of American Jews, she tells him to pay attention to his own happiness instead. "Don't you think," she wrote her father, "[that] you've already given enough to the Jews, and you need to start living for yourself a bit now?"

I love the early part of this exchange because it shows the differences between what children and their parents value. I also find it resonant because many American Jews today are wondering if the American Jewish experiment will endure in the context of growing antisemitism on both the right and left and struggling to determine where they might go and/or what they might do if it is no longer viable.

What do you hope readers take away from "Promised Lands"?

I hope to introduce readers to women's history, a history of American Zionism, Reconstructionism, and American Jewish religion and identity. I want them to understand how a generation of women coming of age following women's suffrage used travel to enhance their agency and self-expression within socially acceptable parameters. I also seek to convey to readers what Zionism meant to this cohort of American Jewish women, and how and why that connection to the Land of Israel became so important to their communal work in American Jewish institutions when they returned.

The personal and family nature of this story – as well as its focus on a young woman coming of age and on relationships between parents and children and among siblings - helps “Promised Lands” to serve as an intergenerational bridge for those who are trying to understand what Palestine/Israel meant to their ancestors and what Zionism might mean to them today. In the aftermath of Oct. 7 and the ongoing war in Gaza, many people are looking for accessible ways to learn about the origins of an increasingly contentious topic: American Zionism. My hope is that Promised Lands provides a path for understanding.

Reported by Mandee McCullough

Photos submitted