Chemists Discover Bright Idea for New Lighting Material

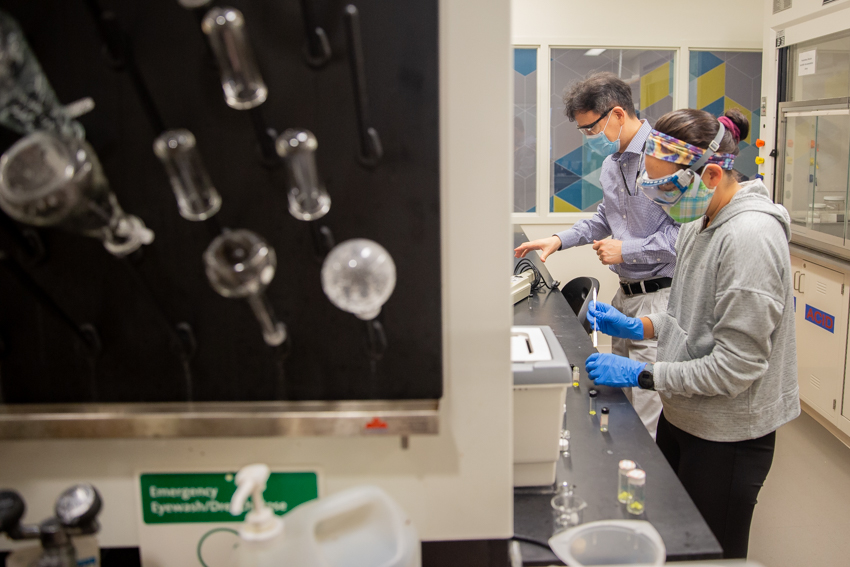

Galloway, N.J. - Senior Chemistry and Biochemistry major Kathleen Ngo discovered a bright idea for a new type of light source after using an unexpected chemical during her research with Wooseok Ki, assistant professor of Chemistry.

Ki’s research looks for alternatives to rare earth elements that can be used to synthesize the phosphors that illuminate organic LEDs, which are used to light digital displays and indicator lights.

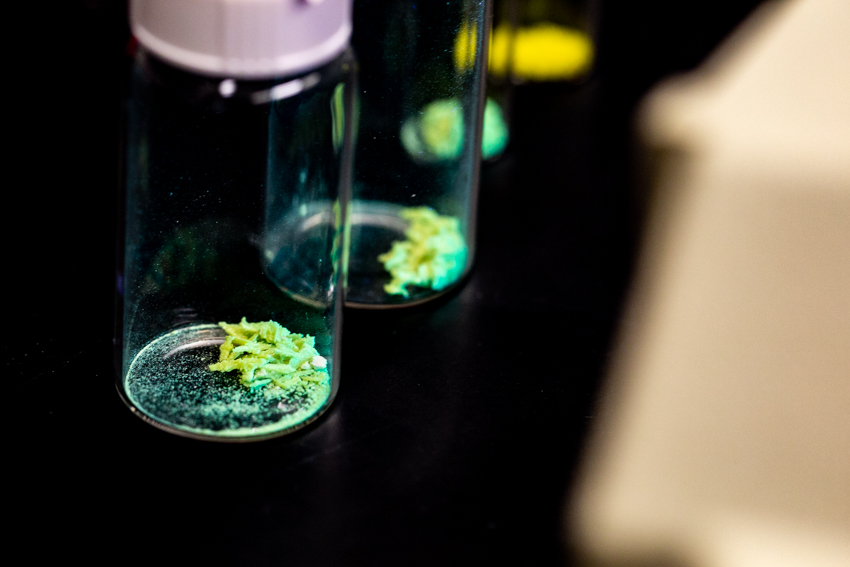

The periodic table of elements is where Ki started his search. Tin is an affordable and abundant element that can be bonded to an organic molecule to make a metal complex. When the precursors of a metal complex are mixed with a liquid solution at room temperature, crystals grow within a day. The sparkly crystal is a phosphor, and when UV light hits the crystals, they luminesce.

Ki and Ngo had been creating tin chlorine phosphors, a known compound that glows a dull yellow, until Ngo tried something slightly different--she used one different chemical--that resulted in a tin fluorine phosphor that glows brighter and green.

To observe the glowing property, Ki turns off the lights in his lab and holds a UV

lamp above test tubes filled with the phosphors.

To observe the glowing property, Ki turns off the lights in his lab and holds a UV

lamp above test tubes filled with the phosphors.

To turn this discovery into a complete organic LED, a device must be fabricated to house the phosphor and expose it to UV light. Ki’s colleague Teresa Atvars at the University of Campinas in Brazil is looking into this next step.

Thomas Edison worked to perfect the incandescent light bulb at his Menlo Park laboratory in New Jersey and patented designs in 1879 and 1880, but research continues today to improve efficiency. Those early bulbs consumed a lot of energy, much of which escaped as heat, explained Ki.

Edison tested thousands of plant fibers in search of a heat resistant filament that would burn for an extended period.

“I love to synthesize new compounds, and I’m very interested in looking at how a chemical structure affects its properties,” said Ki, who added that great things can be learned when these relationships are studied.

“Chemistry asks the questions of how and why, and those answers can be used for practical applications. I want to see the final application,” Ki explained.

The greatest reward in teaching Chemistry is seeing a student complete a general chemistry class and find something that interests them so much that they switch their major, he said.

Prior to teaching at Stockton, Ki also taught at Rutgers and was a research scientist at Siva Power in Silicon Valley, California where he worked with thin film solar panel technology.

Ngo's research with Ki was supported by a Board of Trustees Fellowship for Distinguished Students.

Growing up, fun science experiments were the norm. Ngo's parents are chemists, and she fondly recalls her physics circuit kit and experimenting with food.

When she arrived at Stockton, Ngo was focused on pursuing a medical path, but her chemistry classes quickly showed her how much she enjoys synthesizing inorganic compounds. She's now focused on blending her two passions.

She noted that Cisplatin, an anti-cancer chemotherapy drug, is one way that chemistry is helping to create medical treatments. And some phosphors are antimicrobial and can kill viruses and bacteria.

There is a lot left to be explored and new applications can be discovered, she explained.

After Stockton, Ngo wants to pursue a PhD to become a professor or work in the industry.

Ki and Ngo are the first and second authors on the research study, which has been published in the peer-reviewed journal "Chemical Communications."

Reported by Susan Allen